A Reader Asked:

Q: I keep getting trapped in side control. Sometimes I can’t even get my hips loose to attempt an escape. Some of the guys I train with are really good and get so tight, epecially trapping my hips between their knee and arm, that I can’t move my hips at all. I keep bridging but to no avail. I know a few good escapes that I usually have a lot of luck with, but I wanted to know if there are any little tricks for loosening up the guy on top. How can I loosen the knee and elbow from my hips?”

My answer:

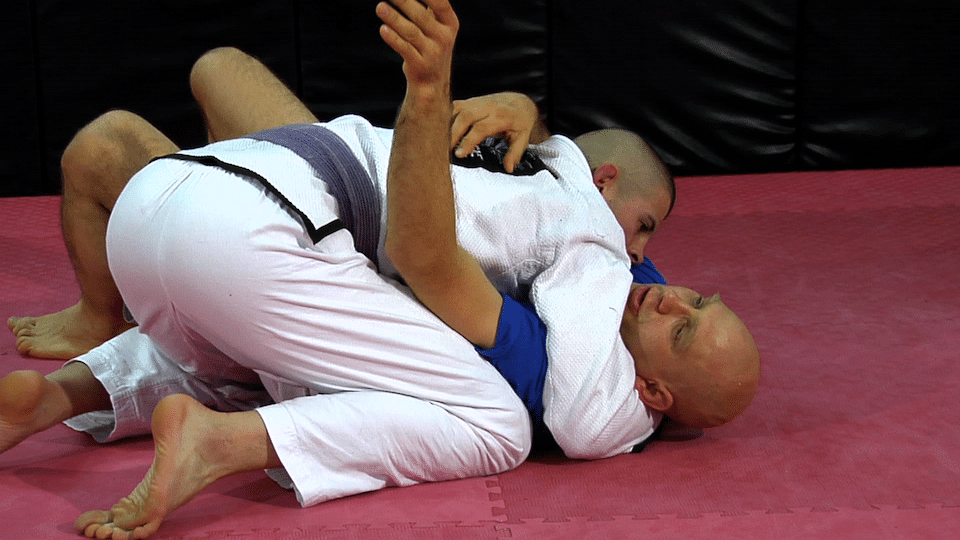

It sounds like your opponents are controlling you in side mount by sandwiching your hips with a knee on one side of your hips and an elbow on the other. This is a good pinning position, and I use it myself fairly often.

First we’ll review a bit of theory:

TWO ESCAPES

There are two fundamental escapes from sidemount:

- Putting your opponent into your guard

- Coming to your knees (aka turtling).

THREE MOVEMENTS

To set up these two escapes you have you have 3 basic hip movements

- Bridging (lifting your hips up and/or into your opponent)

- Shrimping (moving your hips away from your opponent)

- Turning (moving your hips so they face the mat)

MANY POSTURES

In order to use these 3 movements to set up the 2 escapes efficiently you need to fight for posture on the bottom. One of the most important postural issues is where you place your hands and arms – call it gripfighting for the positionally disadvantaged.

Posture on the bottom is a huge topic, and all I’ll say here is that you need to do things like hide your arms so they aren’t susceptible to jointlocks, but ensure that they are in position to push your opponent to make room (e.g. by placing the lower part of your forearm on his neck or on his hip).

SOME STRATEGY

OK, now I’ve given a crash course in sidemount escape theory, let’s try to look at your situation specifically.

First of all I’ll give you some bad news: at a higher level bridging or shrimping rarely work in isolation. It is the bridge that sets up shrimping, and shrimping that sets up bridging. In practical terms it means that you might bridge HARD into your opponent, and then move your hips away and try to come to your knees or place him in guard.

Secondly, reading between the lines it sounds like you are focussing on putting your opponents back into the guard. It might be time to diversify your escapes by trying to come to your knees more. If his elbow is low enough to control your hips then it should be possible to turn belly down.

If he was keeping his arms higher and concentrating on locking down your upper body and arms, then turning to turtle might be a lot harder.

It is true that coming to your knees exposes your back and that you may end up rear-mounted, but the turtle can be a good thing too. Many people go to turtle and then immediately pull guard from there – they don’t really hang out there, just pass through it briefly on their way to pulling guard or half guard.

If you are more adventuresome you can also try sweeps, takedowns and submissions when turtled: Sakuraba is a fighter who did this very successfully at various points in his MMA career.