Introduction

There are many similarities between the sport of Submission Grappling and the classical Japanese Ju-jutsu systems. Both arts emphasize grappling over striking. Both arts recognize the importance and efficiency of ground-fighting. Both arts employ chokes, armlocks, leglocks and other submission holds to defeat opponents.

Despite these similarities, however, there are profound differences between these martial arts. They utilize different strategies, techniques and training methods. The purpose of this article is to examine both arts, side-by-side, and see what similarities and differences emerge.

note: the word “Ju-jutsu” has many different spellings in English. For this article we have chosen to use the spelling “Ju-jutsu” to differentiate it from Brazilian “Jiu-jitsu”.

Submission Grappling

Submission Grappling is a new sport with a long history. The object is to submit your opponent using a variety of joint locks and chokes, or to win the match on points. Competitions in this sport resemble Brazilian Jiu-jitsu competitions, although competitors do not usually wear gis. This lack of gi increases the amount of speed and athleticism required, and it also limits the sweeping and submission options of the competitors.

Submission Grappling is mainly based on Brazilian Jiu-jitsu. Brazilian Jiu-jitsu descended from pre-World War 2 Judo, which itself was heavily influenced by the classical Ju-jutsu systems of medieval Japan. The influence of Brazilian Jiu-jitsu can be seen in the types of positions and submissions most commonly used in the sport.

Other grappling arts have also influenced Submission Grappling. The most common takedowns come mainly from freestyle wrestling. The prevalence of leglocks shows the influence of such arts as Sambo and Catch-As-Catch-Can wrestling (the ancestor of today’s ‘Pro Wrestling’). Many of the top Submission Grappling competitors also compete in mixed-martial-art or no-holds-barred competition, and this brings a certain intensity to the sport.

Submission Grappling is very similar to the grappling required for mixed martial art competitions such as the Ultimate Fighting Championship or the Pride Fighting Championship in Japan. Positions and maneuvers that would be advantageous in a real fight (such as passing the guard or achieving the mount position) are rewarded by the point system, even though striking is not allowed in competition.

Training in Submission Grappling typically involves significant amounts of sparring or ‘‘rolling’’. Live training against a resisting opponent is considered invaluable in developing the skills and attributes considered essential for high-level performance in real-life situations.

Classical Ju-jutsu

Ju-jutsu is a term used to describe a number of different close-quarter combat systems developed by samurai. Initially Ju-jutsu was only a supplement to fencing, spearmanship, and archery – weapon arts were the primary focus of medieval warriors and unarmed combat would have been the very last resort on the battlefield. Ju-jutsu was designed for use in melee combat when weapons had been broken or rendered useless by the close

range of the combatants. Early Ju-jutsu focused on lethal armored grappling techniques and the use of improvised melee weapons.

The classical Ju-jutsu techniques in this article come from one of the oldest of the classical systems: Takenouchi-ryu. It was developed by a warrior named Takenouchi Hisamori during Japan’s Warring States Period (1467–1573). The techniques demonstrated in this article are from the Bitchu-den lineage of Takenouchi-ryu, which is led by 16th generation headmaster Ono Yotaro-sensei.

This style emphasizes unarmed combat skills as well as training in the use of a variety of classical weapons such as the long sword, short sword, dagger, long staff, glaive, and sickle & chain to name a few.

The classical Ju-jutsu leglock, armlock and choking techniques shown in this article are classified as Yoroi Kumiuchi, or armored grappling. These techniques taught the samurai how to grapple when wearing armor and struggling with an opponent wearing armor. The emphasis is on jointlocks, chokes, and strikes that would attack portions of the body that armor did not cover, or using the extra weight of the armor against the opponent.

Training in classical Ju-jutsu is done by way of kata. These are pre-set forms involving two partners (and in some cases more) in various combative scenarios. The kata teach techniques and to demonstrate combative strategy while developing both physical and psychological attributes. The emphasis on working within pre-arranged sequences allowed the use of otherwise lethal techniques and weapons at full speed. In so doing, the incidence of injury is rare despite the techniques being utilized.

Differences between classical Ju-jutsu and Submission Grappling

The differences between Submission Grappling and classical Ju-jutsu can be divided into several categories:

- differences in strategy,

- differences in techniques,

- differences in training methods.

There are various historical and cultural reasons for these differences, and these make the study of either art such a unique experience.

1 – Strategic Differences

The goal of Submission Grappling is to submit your opponent or defeat him on points. The goal of classical Ju-jutsu was to win on the battlefield, usually in the presence of weapons and multiple attackers and often encumbered by armor. These divergent goals lead to quite different strategies.

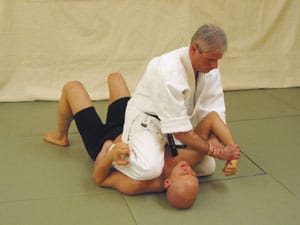

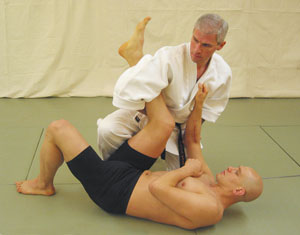

Submission grapplers and the medieval samurai had different concerns while grappling on the ground. Countless modern-day competitions have proven that the ‘rear mount’ (illustrated by the modern choking sequence shown above) is a very powerful way to control an opponent. In this position an opponent is very vulnerable to a number of submissions and has extremely limited options to escape and counter-attack. This position is not favored in classical Ju-jutsu, however, because disengaging from an opponent could be difficult to do quickly. The knee in the spine control, although less secure, could be abandoned faster if a second attacker suddenly engaged the samurai.

Similarly the presence of weapons is an important strategic consideration. Classical Ju-jutsu teaches many defenses against wrist grabs. Some modern martial artists find this emphasis strange, given that so few confrontations begin this way today. In the sword culture of medieval Japan, however, wrist grab defenses take on a new urgency – a person grabbing your wrist may be trying to draw their own weapon and stop you from drawing your own. Furthermore some techniques involve controlling an opponent’s wrist and then using his own weapon against him. In medieval Japan wrist grabs were a big deal, and this is reflected in the techniques of classical Ju-jutsu.

2 – Differences in Technique

There are many similarities in the chokes and joint locks of Submission Grappling and classical Ju-jutsu – there are, after all, only a limited number of directions in which you can bend someone’s arm, twist someone’s foot or squeeze someone’s neck. Nevertheless there are some broad general differences in how the techniques are applied.

Classical Ju-jutsu utilizes some pressure-point attacks, whereas modern grappling tends instead relies on structural attacks. As an illustration of this principle, consider the leglock techniques linked to below. The classical Ju-jutsu man is crushing the calf muscle and attacking a nerve pressure point midway down the lower leg. In an otherwise similar attack, the submission grappler is attacking the ankle joint itself, threatening to tear the ligaments, muscles and tendons that attach the foot to the lower leg.

This reliance on pressure points is a divergence between old and new. The use of pressure points in classical grappling is due to a variety of factors. In some cases the point being attacked is in a location not very well covered by the armor of the era. In certain instances the pressure point attack is utilized to harness the pain response and create openings for subsequent submissions or strikes. In addition, certain very dangerous pressure point attacks, such as gouging the throat or eyes, are illegal in grappling competition due to safety concerns. Finally a submission grappler might argue that pressure points are unreliable, and that someone with a high pain tolerance could ignore such an attack.

Another difference occurs after a successful submission has been executed. In modern grappling a successful submission ends the match. In the classical Ju-jutsu context an opponent with a broken arm or dislocated leg might still be dangerous. As a result the classical Ju-jutsu kata often follow a submission with additional strikes and maneuvers designed to make absolutely sure that the opponent is no longer a threat.

The presence or absence of armor is another large factor in determining how techniques are executed. Limited mobility, protection of certain joints and body areas, and the use of an opponent’s armor against himself are all factors the samurai had to contend with. Consider the classical leglock shown in this article: after a successful leglock Alex kicks his foot into the air, simulating moving the armored flap protecting the groin out of the way, before dropping his heel into the groin to finish the confrontation.

3 – Differences in Training Methods

Ultimately it is perhaps the differences in training method that create the most profound divergences between the old and new approaches to combative grappling. How are the techniques actually practiced? Exactly what method is used to develop proficiency and technical expertise? What is the training ‘culture’? The answers to these questions heavily influence the development and outward form of a martial art.

As mentioned earlier, most classical Ju-jutsu training revolves around repetition of kata, repeating a specific combat scenario with one or more partners. This approach to training is very different from the rough-and-tumble training sessions of Submission Grappling, where sparring is emphasized. Classical Ju-jutsu would contend that the techniques in question are too lethal to practice in an un-rehearsed context. Submission grapplers would

argue that the benefits gained from being able to grapple competitively in training far outweigh the disadvantage of having to use less lethal techniques

The goals of modern day practitioners are also different. Most classical Ju-jutsu stylists today feel that preserving the art in its original state is important, and do not welcome changes to their kata, techniques or training methods. They are very concerned about the history of their art and this is illustrated by the fact that most serious Ju-jutsu practitioner

can usually trace their exact lineage back to a single person in medieval Japan. Submission grapplers, on the other hand, are most interested in surviving and winning while on the mat. If they think that they have found a more efficient way to take someone down and choke them they will rapidly adopt it. Submission Grappling is evolving very rapidly, and techniques fall in and out of favor on an annual basis.

Finally there is a profound difference in the way in which information is spread in the two arts. Knowledge of techniques in medieval Japan was often a life-and-death matter for the samurai. Consequently there was a strong tradition of secrecy, and each ryu or system had its ‘closed door’ techniques that would only be entrusted to reliable senior students.

In the modern world however information can no longer be kept a secret. Grapplers attend seminars and take private classes. Instructional DVDs and video footage of competition is available worldwide. Magazines show a competitor’s favorite moves. Forums on the Internet openly debate the best way to apply different techniques. This is an unprecedented development in the history of martial arts, and is the underlying reason why the sport is growing and evolving so quickly.

Summary

The study of these different approaches to combative grappling can be a fascinating and rewarding undertaking. The classical approach emphasizes issues related to culture, history, and the perils of total combat. Modern Submission Grappling, on the other hand, offers a highly efficient training method to develop skills and proficiency in the techniques of combative grappling. It is the opinion of the authors that practitioners of both arts can benefit by being exposed to the other art and approach.

About the Authors

Stephan Kesting is a martial artist and competitive grappler. He produces cutting edge instructional videos and DVDs. Check out his grappling tips, articles and interviews for tons of grappling information

Alexander Kask is the head instructor at the Shofukan dojo and is the only teacher of Takenouchi-ryu in Canada. He is author of three publications on the Japanese language and is an attorney based in Vancouver, British Columbia.